I’m often perplexed by the question “After we die, what’s next, or where’s next?”

What’s your answer to that question?

Some answers relate to living in a mansion, or a Kingdom, on a throne perhaps, with prosperity being an alluring feature. Living forever is a constant but how and in what form?

Death is a transition point, not a terminus.

Following the series of talks on Euthanasia and then ‘What is a Good Death’ by the President of the Mosque and myself in Todmorden, the questions remain. Perhaps they should as there is a vagueness about the whole issue – that is why we have faith. I hear that the opposite to faith is certainty, and this may be one such example of this.

So what in the eyes of faith is a good death?

Living and living well was always an important aspect to the Hebrews. Sounds good to me as well.

When we die many might expect me to say that we go to Heaven – where is it, can you point to its location?

Is it like a heavenly piece of chocolate cake or a holiday location which is described as heaven?

Even Leslie Howard who spoke of being “I’m in Heaven”, and Belinda Carlisle who sang of “Heaven is a place on Earth”, both which we hear here (via the hyperlinks), both spoke of heaven as being in relationship.

Here is the Greek understanding of Heaven, a shell enveloping the Earth’s surface through which Angels and weather could enter to the earth. It reminds me of the Simpson’s depiction of Springfield, from the 21st C… in fact this is The Simpson’s depiction!

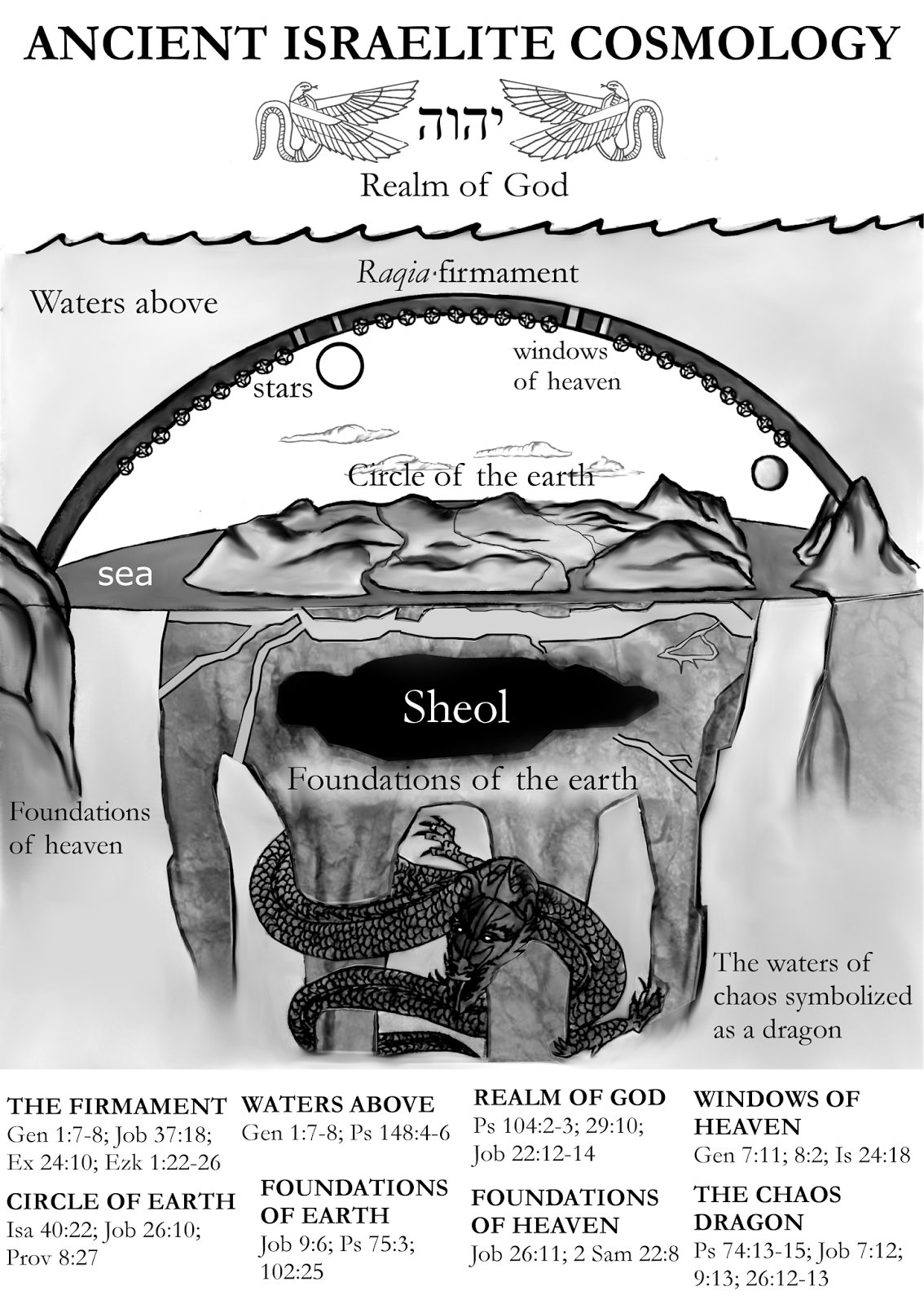

According to the Hebrew people, there was a separation of the waters above and below the Raqia or firmament, above which where God would dwell. God is above, the Earth below the Raqia or shell. Sheol, the area of darkness lies below the Earth. It is where they thought everyone, the good and the bad, would good to be with God. Sheol was later translated into Greek as Hades. When Jesus was crucified at Gehenna, the fiery rubbish heap outside of Jerusalem, Hades became Hell. They are all perceived to be interlinked – below the earth, hot and fiery: although it all originates with the Hebrew understanding many centuries before Christ.

It appears a bit far fetched when we look at the advances of cosmology today, but even the Book of Genesis, written around 500 yrs BCE, not at the start of time, seems to infer that both Heaven and Earth are entwined, not separate. This was their interpretation of what the world looked like. We can criticise but what can we take from this perspective? they, Heaven and Earth (us) are in relationship not solely based upon location.

Now the Hebrews understood our lives to be of separate parts: body, soul/spirit and mind. Adam was created from the dust, and life was breathed into his nostrils, so life is separate to our bodies formed of dust. You may have heard that phrase at funerals and at interments in the cemetery: “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust, in sure and certain hope”. Our bodies, made of dust, return to dust, but what of the soul/spirit?

So as Adam was created, and we are created in God’s likeness:

“who amongst us looks the most God-like?”

I wonder whether God’s likeness is what we see, in our bodies? As a society we may consider beauty to what we see.

Hence those with alzheimer’s/dementia can still be seen as fully human, not diminished, despite their mind beginning to fade.

What of that idea that we are to be in Heaven, as what and in what form?

Where did the idea of the Resurrection start?

This stems from the story of Daniel, the one in the lion pit, which speaks of those who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake when Michael (angel) appears, albeit it does add ‘some will arise’. Daniel 12:2

This was very controversial at the time and even in the latter portion of the first century many different Jewish groups had very different ideas: Sadducees didn’t believe in any life after death; whereas the new Christians did.

Paul, then who saw Jesus on the Damascus Road, wrote far earlier than the Gospels were written, spoke of this resurrection as an essential part of the Christian faith, it is a seemingly load-bearing stone. Interestingly when speaking to the Athenians he mentions the Resurrection but not the Cross.

What are we like here on Earth and in Heaven ?

What if your life has been marred by disability, both seen and unseen, or disfigurement; are we to perceive that in the afterlife we are to return with the very same bodies? This may be perceived, in retrospect, as an ableist comment. A recent report cited that 1 in 13 respondents wanted to retain their disability in Heaven.

Paul writes that currently our bodies are perishable, dishonoured, weak and physical. Well as the years pass by, we may all see that our bodes don’t regenerate, don’t return to health as they did in the past, we may not be valued in society as we have done in the past, our strength evades us and we are less mobile. So what of the future? Are we to return beyond the constraints of the 3 dimensions we view today because that we are then of spiritual form?

Here’s what remains of my Dad, [I showed the box in which the remains of my Dad lie] yet to be interred. Where is he now?

The Bible speaks that we to be imperishable, glorious, powerful and spiritual. It is this last word that strikes me as so powerful and also linking many thoughts from Pushing Up Daisies talk [a festival where we talk intentionally about Death : it is for all faiths and none] this week.

When my mother-in-law died we were advised that a window had been left open for a reason. This consideration that we are more complex than we first thought, what we see are our bodies, physical and eventually frail, we associate our value on what we can do and how capable we are, when possibly we need to reconsider who we actually are. For those within the LGBTQ community, who identify due to their sexual orientation and gender, not one that they were assigned at birth visually, here we may also see people as God intended. [I’m alluding to transgender (and intersex) individuals who due to measurement at birth are assigned their sex]

A Good Death to the Hebrews had three features:

– a long life, and so in the Scriptures you have people living to over 900 years.

– leaving at least one son to continue the family name, seems a bit prosperity led here but how important is your surname, that family linkage to you?

– a good burial, for as long the body, the bones existed, could be kept safe – no cremation then – God could still be with them.

Oddly, Jesus’ death can be seen as not a good death: he died prematurely in his 30s; he left no son; and the tomb was not his families. Nor can we guarantee this for us.

So what? What was so good about this form of death?

It was felt that if one had had a good death then your future would be good as well.

There was already some belief in resurrection.

I recall that when my Father was near death I spent the last few days with him. He was unable to get out of bed and was being fed. His speech was difficult, laboured but when my brother rang in from overseas, his face changed. There was joy, his hand gripped mine tighter, there were murmurs – attempts at speech. As the evening drew to a close, I went to pray with him. I spoke honestly openly about our lives, offering a prayer to God about the future, giving my Father ‘permission’ to leave us, it was OK to go. Soon after, his breathing slowed, and then he died. It was a peaceful moment. One in that I believe he knew that he was released from any bonds here, to go to God, to join others who have gone before. It was a transition point. The body, recently moving gently had now become motionless in front of me, but the spirit had now gone.

To me this was a good death: at peace having achieved what could be achieved, the family and friends could remember him, and the spirit had moved onwards.

Death is a transition point, not a terminus.

For the theologians, this is an important eschatological point. However we die here on Earth, what is next for us? Might we view death as that transition point, a bus stop on this journey but certainly not the terminus or bus station? How does that change our perception of death? Does the fear of that perceived terminal end drive us towards making decisions: what if that fear did not exist? Our faith highlights that we believe there is a future beyond death. It is a belief that has been in existence for millennia.