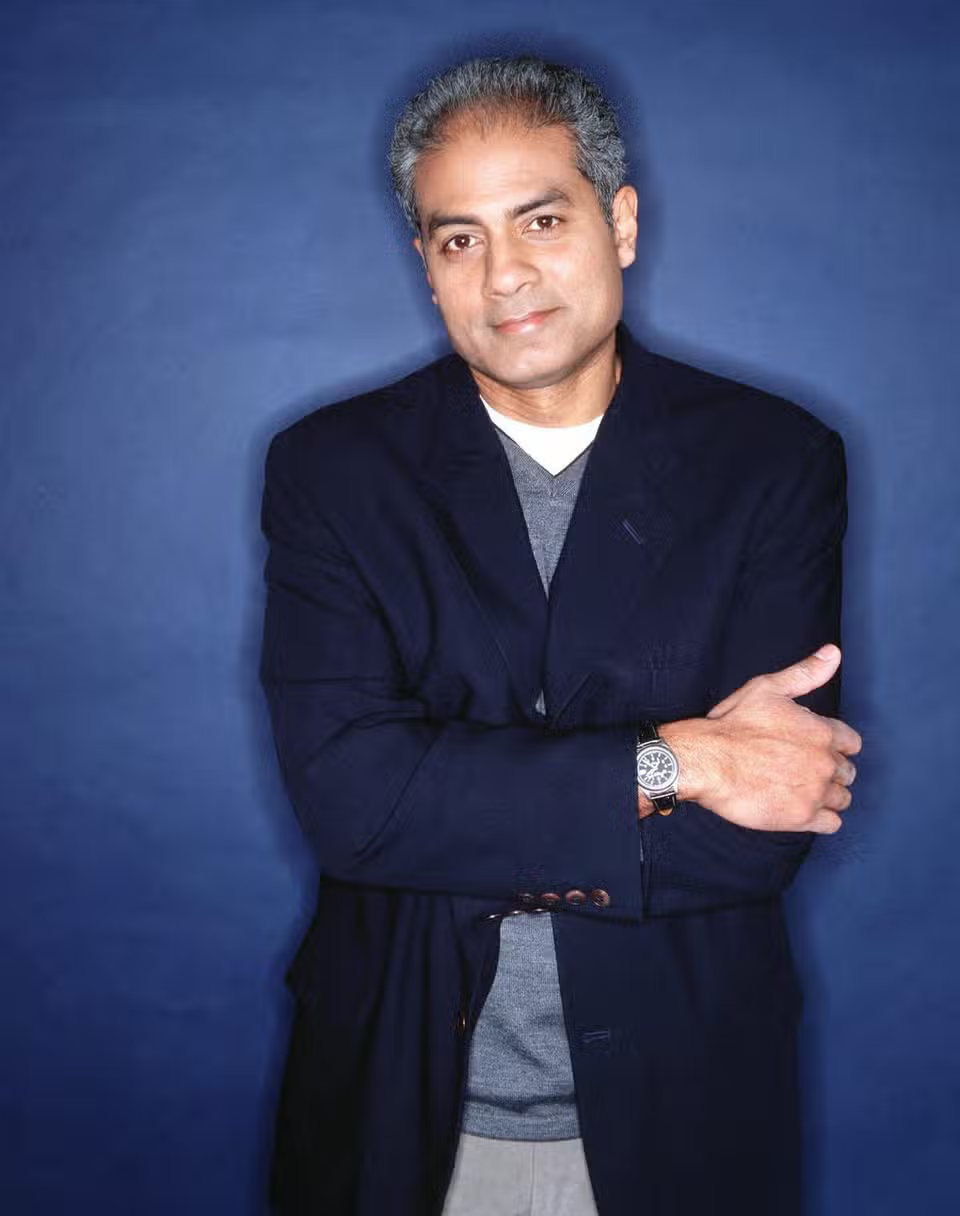

The death of George Alagiah, the BBC newsreader and journalist, made front page headlines, whilst also receiving emotional coverage across the main media broadcasts. But in the words from this celebrity, we also heard such hope when facing death.

“My life, for what it is worth, is divided into pre-cancer and post-cancer. The weird thing about a bowel cancer journey is you don’t really know the beginning and you don’t really know the end”.

Stages of life?

He divided up his life, when looking back, into those 2 clear stages: pre- and post-cancer, but there was also a central stage: that of the period when diagnosed with cancer. Of seeking to come to terms with the consequences, with the inevitability of death – as will we all.

“So I know the day I was diagnosed with bowel cancer, but I don’t know when it started. Because I was at the top of my game, I was having a fantastic time at work and home, and then suddenly you hear those words ‘I’m sorry to tell you Mr Alagiah, you’ve got bowel cancer’. “At first when you’re told, you don’t know how to respond and it took me a while to understand what I needed to do.”

Quotes from Evening Standard

Is this grief?

We may know of those who have been diagnosed with a life threatening condition. The shock of the news is emotionally akin to grief itself. That denial; anger (why me?); pain not only from the condition but what might have been; depression, as we might sink in on ourselves; and then acceptance (is that really possible?)

“For me, I had to get a place of contentment and the only way I knew how to do that was literally to look back at my life. Actually, when I look back to my journey, where it all started, looked at the family I had, the opportunities my family had, the great good fortune to bump into Fran who’s been my wife and lover for all these years. The kids that we brought up:

it didn’t feel like a failure.”

Finding contentment

When we look back at our life, can we do so without feeling as if we are moving things into two camps: the good and the bad times? If we were to look at the ‘bad times’ we may infer guilt and then feel shame for what we perceive we have done. Our interactions with others are multi-facetted: they involve many people, all with their own issues and perspectives. How can we really tell now what the situation was, and infer responsibility? Shame is a huge weight we can carry upon our shoulders, a millstone that we might be able to release so we can move forward, unhindered.

Can we forgive others and ourselves for the past, to enable this release?

“I wish I hadn’t had cancer, obviously. But I have cancer and I’m glad of the things I’ve learned about myself and about my community, my friends and my family as a result.”

In this process of looking back on our lives, we might well learn more about ourselves. Society drives us forward at a relentless pace, so fast that rarely might we have that time to pause and take stock of the relationships we have: some fleeting, some long-lasting. We can then possibly note the strengths of those bonds, the ones that carry us onwards.

“I have gotten to a place to see life as a gift. Rather than kind of worrying about when it’s going to end and how it’s going to end, I’ve got to a place where I can see it for the gift it is.

I feel that gift keenly every morning.”

Whether we see this gift as physical and/or spiritual, it is still a gift.

Hope when facing death

George Alagiah saw the end of life not as a point of time but the conclusion of the gift of life that he had experienced with his wife, children and grand-children (and from the comments online, colleague and friends). I wonder if we might be able to consider the impact of others, the gift that others have brought to our life, and also dare to imagine the impact we have brought to others – that they would also reflect on the beauty of our lives on their life. Death has been seen here in the entirety of life itself.

I found the dialogue interesting and I enjoyed