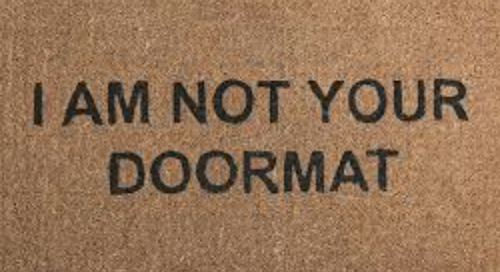

Often Church folk are told that they should turn the other cheek, and love your enemies. It’s quite a simple adage, possibly not so simple to apply to ourselves. But was that to whom it should apply? Are we to be a doormat to others?

Lent

Within Lent we are all approaching a focus, that of Easter. That Easter week, starting with Palm Sunday, is just so full of conflicts, many of them possibly pre-planned. It doesn’t seem to follow my understanding that we are not to resist the “evil-doer”. Perhaps we need to look again?

I’ll be brief on the details here as that might affect our later reading of the events when we come to them. Palm Sunday, that riding into Jerusalem on a donkey – what’s that all about? Given it’s Passover, many Jews would have thronged the streets to celebrate the memories of the fleeing of Egypt into the promised land. The Romans were also aware of the possible conflict; hence, additional troops would have been sent to placate the masses.

The week preceding Easter

Jesus sends his team onwards to get a donkey (or two, if you are Matthew) – it’s very pre-planned. So just as the Roman General strides into Jerusalem on a white steed, surrounded with pageantry and regalia, Jesus enters the city from the opposing gate on a donkey. (Zechariah 9:9-10) Why?

Rome ruled this land, using local elite collaborators: Galilee by Herod Antipas, Judea & Samaria by the Temple authorities, and Jerusalem under a High Priest appointed by Rome. The agrarian society had been created and sustained by the rich and wealthy, oppressing the poor. The popularist Herod the Great et al spent vast suns of money on their lavish lifestyle. This needed money from the locals, plus they also needed to pay Rome an annual tribute. Poverty wasn’t very far on the horizon for many. Did anyone have power to be anything other than be a doormat?

Why didn’t they do something?

They had tried. In the 20CEs they had revolted against Governor Pilate in Caesarea when Roman troops held aloft large banners with the Emperor’s image. They offered their necks to be severed by the troops? Pilate declined. In the 40CEs Emperor Caligula wanted to erect a large statue in his honour inside the Jerusalem Temple. The Jews were organised. They set themselves into 6 groups: old men and young men, older women and younger women, boys and girls – and offered to ‘willingly to be put to death’. The local Roman official declined. Not really ‘doormat’ stuff, amazingly brave in fact.

So Jesus?

Jesus had rode into Jerusalem, a symbolic act of defiance. This ‘symbolic act’ was key. On the Monday Jesus ‘cleansed the Temple’ – well it wasn’t really cleansed more like briefly caused a disturbance so he could teach. Yes, we can focus upon the whips and the fleeing money-lenders, but they’d be back. Furthermore, cause too much of a rumpus, and the Roman troops would calm the scene using their own particular ‘ways’…

On the Tuesday, Jesus is in heated arguments with the Pharisees who demand ‘by what authority’ does Jesus have? Jesus speaks of the Vineyard and the Tenants, and lastly how much tax should be given to Caesar. All of these three scenes focus upon dominion and power. Not power of the individual, but of the ruling Roman authorities. Do we go quietly, or follow God?

If some German Christians went along with Hitler’s Confessing Church, were they seeking to acquiesce to the current political situation or really contemplate what exactly the political ruler was desiring? Does the evangelical church in the USA, those whom support the past President (#45), see the Gospel’s ‘preferential to the poor’ in what he was preposing? Do any of us see a division between the Gospel and the political situation in our own countries? It isn’t about one political party or another, but what do they really stand for, can we be counted ‘in’ on that reckoning?

‘An Eye for an Eye’?

We may often see this as a passive acceptance of wrongdoing. But how many eyes do you have, let alone teeth? This isn’t about personal relationships but the political realm. When Jesus responds to the clause ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’, an accepted Jewish principle, he offers ‘do not resist an evil-doer’. What the English doesn’t emphasise is that the resist needs to become ‘resist with violence’ to be more accurate.

When responding with violence we become equal with the actions of the aggressor.

When Jesus speaks of taking up thy cross, Mark 8:31-38, he is speaking of not retaliating in kind, but refuting the dominion and power evident with the Roman ruling authority, knowing that God’s kin_dom is at hand.

Be a Doormat?

If we are to see Lent as different, as a foretaste of the celebration of Easter, we also need to consider what it is to include politics into our understanding. Where the poor are downtrodden, where the wealthy are raised up, given preferential treatment, where power is exercised unfairly, there we also need to be – protesting. However, it isn’t with violence, but symbolically redefining the contours of the land, our society.

Church, however you define it, is not separate from our political structures but is a necessary part of our expression of our faith. If our Church includes a hierarchy which belittles the poor, whether that be financially or ethically, which provides additional support to the wealthy, then our faith should make a difference to how that is changed.