We come to our fourth Sunday in Advent. Its focus is Love. The passage is Luke 1: 39-56 and this contains the Magnificat, the song of Mary to her relative Elizabeth. But let us stop there, and reflect a while on these two women.

| Elizabeth | Mary |

| born in the line of Aaron | descendent of no one of note |

| deemed to be righteous | not described as righteous nor blameless |

| lives in Jerusalem | lives in Nazareth (did anything good come from…?) |

| married to a priest | unmarried |

| the pregnancy raises her status | pregnancy infers socially marginalised |

| Non-Virgin | Virgin? |

It’s like chalk and cheese. Nevertheless, these two women get on like a house on fire, and soon Mary is singing a song to Elizabeth. It feels familiar, akin to 1 Sam 2:1-10, Hannah’s Song? A song of liberation, a revolutionary proclamation of conflict and victory?

Given that the author of Luke’s Gospel was writing 40-50 years after the resurrection, let alone the birth, I wonder where did they source their information. Scholars inform us that these stories were handed down orally. Luke wasn’t writing a Gospel for us to read, but to record for a Roman called Theophilus – whom was the intended recipient of both Luke’s Gospel (recall that each of the Gospels weren’t attributed to anyone in particular until the 2nd C) and the Book of Acts. So, why would the author of this particular Gospel write about a meeting between relatives?

Both Matthew and Luke – who actually mentioned the birth of Jesus, for nor did Mark, John and even Paul who was the one of the first to write anything (which we have within our Bible) about Jesus – wanted to provide a firm basis for the reasoning for this birth. Matthew tells the tale of miraculous stars leading wise men, not 3, of the Holy Family travelling to Bethlehem, and of escaping to Egypt. Luke speaks of angelic chorus lines, shepherds coming to see the newly born babe. When the word manger is present, our English translations suggest that it is a barn with animals, albeit none are mentioned. Manger can best be translated as a guest room, a room adjoining the space for the family where animals could be present. In this case, the Holy Family find respite there.

Back to the Magnificat

This song from Mary is known as the Magnificat. It is a combination of Old Testament allusions from specifically the Greek translation, known as the Septuagint or LXX. It speaks of a call to stand up, resist and see victory. So much so, that it was banned from being read in Argentina, Guatemala and India, as it was seen as fermenting non-violent resistance to the ruling power – that might well resonate with Mary. The Mothers of the Disappeared in Buenos Aries cried out in anguish: “The women’s pleas for help fell on the deaf ears of the Church, most labor union leaders, the business community and the press.” Can we hear that cry?

So what?

I could focus upon with the stereotypical story of love at Christmas time, of Mary and Elizabeth overjoyed at the prospect of bringing up two children, and of their hope – see previously – that these were special.

How the author was aware of this story I leave to the historians to link together the various texts we have, with presupposed texts such as Q. However, we may need to recall that both Gospels that have the Nativity story are inconsistent (discussed here and here) and are struggling to include the prophecy of Micah 5:2 that a child will be born in Bethlehem, and not Nazareth, their home town. That Quirinius wasn’t the Governor of Syria at that time, and that no empire-wide survey was recorded even by the Roman authorities. Just imagine the bedlam caused if every family had to go to their home town? That the killing of the wee bairns in Bethlehem wasn’t recorded, and the flight to Egypt was mirroring Moses, a key predecessor to Jesus. There are more questions here than anticipated presents…

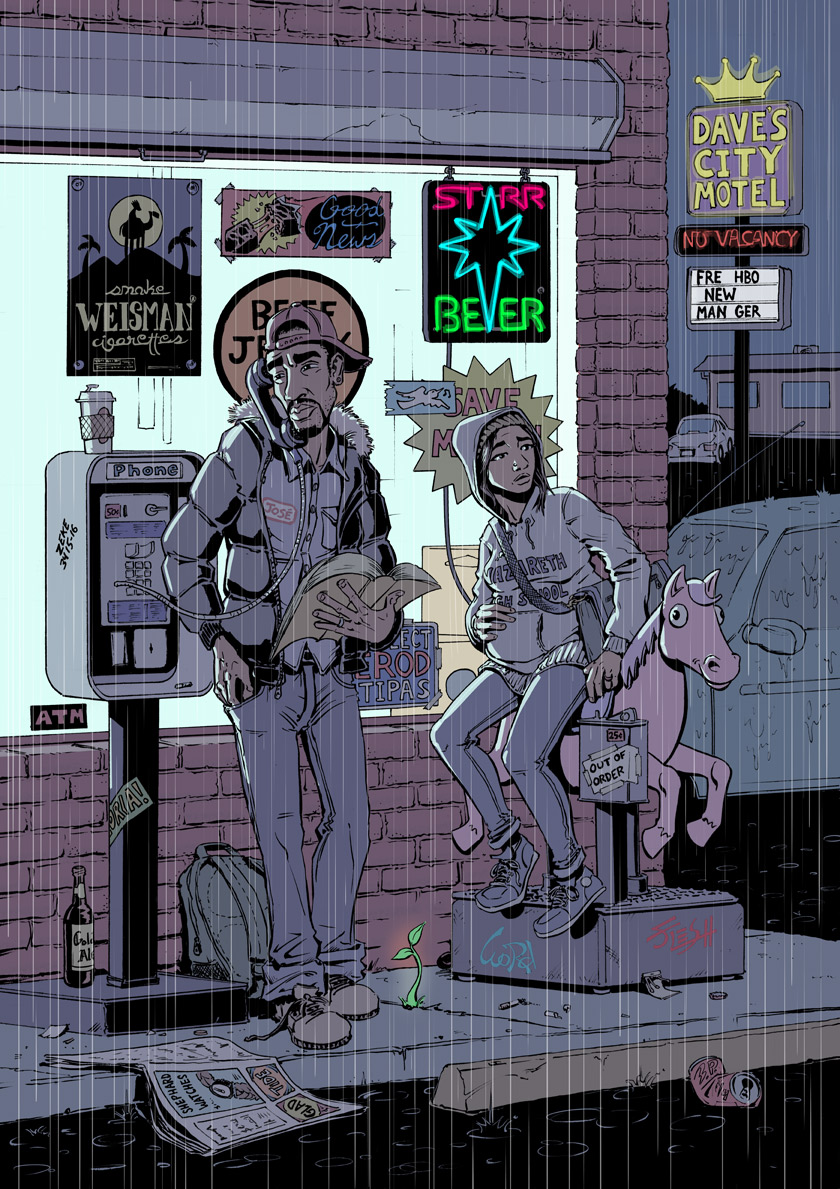

What we may focus upon is the kin_dom envisaged by the authors of the Gospels, that of the message to the poor of the day, those oppressed and victimised. That the opposite is true, and that they are loved. When we hear of political leaders drawing hard boundaries to define their land, to ensure that the capitalistic empire continues to grow, feeding the richest, denying opportunity to the poorest, then we can hear this song for us today. Its notes pervade our world, in all that we can see. That Christmas is driven by Black Friday (or is it a week now?), or Christmas spending frenzies, followed quickly by Boxing Day sales (possibly on Christmas Eve), and then the keenly awaited New Year’s Sales. There is no commercialism in the story of the birth of Jesus. The family needed to find a place for the birth – think today of families who need such a space. Of finding a room which isn’t normally deemed suitable but they’ll take it – can we imagine that today?

The baby is born in Nazareth, with no fanfare. But from all this humble, vulnerable, birth stems such a change, a violent transformation, emphasised in the words of the Magnificat. The call to the preferential for the poor should be heard loud and clear today. Can we hear it?

I never knew that this song from Mary is known as the Magnificat.

Also, I never knew that before the end of British rule over India, the Magnificat was prohibited from being sung in churches.

The British hymn “Abide with Me” was part of India’s Republic Day celebrations until 2021, when it was replaced by the Indian patriotic song “Aye Mere Watan Ke Logon”. The change was made as part of an ongoing process of decolonizing India.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sdyPozsx_6M

Sung by the late popular Lata Mangeshkar on the first Independence Day 15 August 1947.